- Home

- Glories

- Spreading

- Image

- Casket

- Ladder

- Priest

- Beasts

- Unspeakable

- Ages

- Creatures

- Fishers

- History

- Sanctuary

- Revelation

- Righteous

- Proscribed

- Secret

- sheaves

- Cows

- Potter

- Judgment

- Tree

- Impressive

- Meeting

- Bible

- Earthquake

- Captain

- Sabbath

- Team Work

- Storm Coming

- Ricks Story

- Two Crowns

- Loaf Of Bread

- Upon The Water

- Free Indeed

- Deliverance

- J N Loughborough

- Church In California

- Heart Prepared

- Revolution

- Civil War

- Starry Crowns

- Abimelech

- Tennent In A Trance

- Mabel's Dream

- Pins And Needles

- Called By God

- A Furrow

- Camden

- Angel Visit

- Door to Door

- THE ROBE OF PETER

- Dream Come True

- My Dream

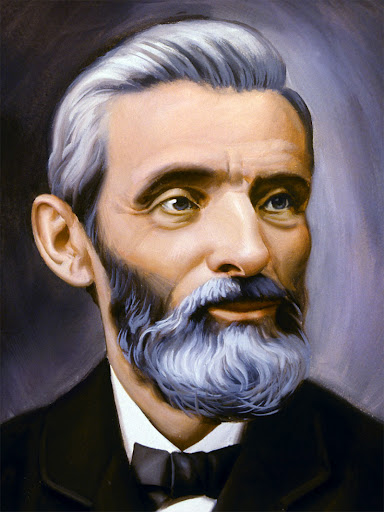

J. N. Loughborough,

Chronicler of Pioneer Days

About the time Joshua V. Himes met William Miller, an orphan boy lived with his grandfather in western New York, and early became acquainted with God through his devout grandsire, who was a class leader and steward in the local Methodist church. This lad, John Norton Loughborough, was born in Victor, New York, January 26, 1832. His parents were Methodists, and his father was a local preacher of that denomination. When John was seven years of age his father died, leaving the family of five children in poverty, and his mother placed the future Adventist leader in the care of his grandfather.

No matter how busy the season of the year, this godly man always took time morning and evening for family worship. The devoted life of this grandsire made a profound impression on the youth, for forty-five years later he recalled that on numerous occasions he had seen the older man rise from prayer, his face bathed with tears, under a sense of God's presence.

Threshers, harvest hands, and other workmen sat in the family circle while the earnest head of the house read a chapter from the Bible and offered a prayer which often changed the carefree, irreverent laborers into sober, thoughtful men. The grandfather rose early in the morning and spent an hour in prayer. Again at night he retired to his secret place to seek power from on high. Often Johnnie, as he was called, heard his name mentioned in prayer, and his early religious impressions were deepened by the faithfulness of this man of God.

In the thirties in New York the Methodists were not a popular group. Some of the neighbors were bitter in their opposition to the grandfather's religion. More than once as they returned from meeting, the boy heard unfriendly people exclaim after the wagon had passed by, "Old Methodist," or perhaps more slurring expressions. Sometimes they lowered the fence, allowing loose cattle to feed on and tramp down the grain while the family was away at meeting. The grandfather would drive out the cattle, put the fence in place, and pray for his enemies.

During the proclamation of Christ's Second Coming in 1843 and 1844, the family accepted Miller's teaching. In the winter of 1843 the family went three miles every night for six weeks to attend the lectures on Christ's advent. On one occasion a certain Mr. Barry preached a sermon on the judgment to an audience of about two thousand. Every available foot of standing room was filled. At the close of the discourse, among the scores who went forward for prayers was John Loughborough. Since he was only eleven years of age, not much encouragement was given him by the Christian workers, and not until some years later did he become an active Christian. He believed the theory of it as far as his young mind could comprehend the subject, however. The Midnight Cry came to the home regularly, and he was much interested in the paper. Often he was sent to take it from one neighbor to another that all who wished might have an opportunity to read it. In this way the future worker did his first service in the advent message which he was to support so untiringly for three quarters of a century.

While residing with his grandfather, young Loughborough had the opportunity of attending a good district school. In 1847 he went to live with his brother to learn the carriage making business. At the end of seven months the brother closed his shop, and the apprenticeship ended. This gave opportunity for the young man to attend the most advanced school in his native town.

In May, 1848, he accompanied a friend on a three-day visit to his brother. While there he heard a stirring Adventist sermon and was convicted of sin. A fearful struggle possessed him for a few hours. Ambitious projects had been fostered in his mind by the school and its associations. On the one hand was the allurement of the world, and on the other was the choice of God's service. His life's destiny was wrapped up in that decision. He saw that his ambitions must be laid aside if God's service were his choice. Once the decision was made, he said, his earthly plans and worldly associations sank into insignificance compared with the work of seeking the favor of God. He accordingly hired out as an apprentice in a blacksmith shop to learn carriage ironing. Shortly afterward, about the first of June, 1848, at a prayer meeting he arose and took a public stand for his Lord and Master.

During the summer months, when business was slack, young Loughborough's employers spent much of their time chatting with the frequenters of the bar at the hotel just across the street from the shop, leaving him to remain in the establishment and watch for customers. Having spare time on his hands, the lad improved these precious moments in studying the Scriptures and praying. Hungry for the truths contained in the word of God, he always kept a copy of the Bible near at hand and delved into its pages when he could do so without being unfaithful to his employers. Often the midnight hour found him studying the sacred pages.

During the summer the young man regularly attended the meetings held every two weeks in near-by schoolhouses. He had not as yet obtained all the evidence he desired that his sins were forgiven. Many times while he was praying in the old coal shed attached to the shop, the duty of baptism presented itself. The conviction became stronger and stronger that in order to be free he must be baptized. Accordingly, about the fourth of July he went forward in this rite. He came forth from this experience filled with joy and with songs of praise on his lips.

The shop where he worked was near the bank of the Erie Canal at Adam's Basin, and directly back of the shop stood pools of waste water from the canal. These became a fruitful source of malaria, which he contracted after some time.

He continued blacksmithing until September, when he was obliged to change his work. There had been only one carriage in the shop during the time of his stay. The main business was that of shoeing canal horses, which was very heavy work for one of his size and strength. This, together with the malaria, brought on sickness which terminated his two attempts at an apprenticeship in blacksmithing. The sickness soon developed into fever and ague. This began with a chill on alternate days, soon increasing to a chill every day, and after two months to two a day.

Two summers' apprenticeship, a term of school, and a long period of sickness left him penniless. Under these trying conditions the conviction came that he should preach the truths he had learned. He felt also an assurance that if he would yield to the "call," he would be relieved of the ague. After a hard struggle with self, he yielded.

In physical weakness, his stock of clothing low, and without financial resources, he put his trust in God, asking Him to open the way. A neighbor had a pile of wood to saw, and Mr. Loughborough arranged with him to cut it as his strength permitted. In this way the budding worker earned one dollar. The kind man also gave him a vest and a pair of trousers. Since the donor was seven inches taller than Mr. Loughborough, who was a small man, the fit was far from perfect. The young man's brother gave him an overcoat, the skirt of which he cut off, making of the garment a substitute for a sack coat. With this curious outfit and one dollar he decided to go into a district where he was unknown and make an attempt at preaching. His brother gave him five dollars' worth of tracts, thinking an occasional sale would help meet expenses. When he was about ready to enter upon his new work, an Adventist friend of his father gave him three dollars to help him on his way.

He journeyed to a community about eighteen miles from his acquaintances, and accepting entertainment from a family friendly to the study of the prophecies, secured the use of the Baptist church for a series of lectures. An announcement of the meetings was made at the close of the district school, and on the evening of January 2, 1849, he gave his first discourse. The house was well filled, and the diffident youth, afraid of failing, handled his subject with ease and clarity.

At this time John Loughborough was a lad of only seventeen summers, who had tarried overnight among strangers but once before. Imagine his consternation to have the pastor of the church in which he was preaching rise on the second evening at the close of the discourse and announce to a crowded house that the meeting house would not be available for any more meetings, since a singing school was starting at once. A man from the audience quickly arose, and intimating that the minister had arranged the singing school for the purpose of shutting out the Adventist meeting, invited the boy preacher to come and preach in the schoolhouse in his district. Five lectures were held in this place. In the meantime, by dint of hard study, he had increased his scanty repertoire of ten lectures and was better prepared to preach the message which he represented. He preached in several schoolhouses to large crowds, for the sleighing was excellent, the beautiful moonlight nights promoted good attendance, and his message was well received.

After a time he returned home to see that his widowed mother had wood to burn. While he was there, the Adventists wanted him to speak to them. They seemed satisfied that he had made no mistake in beginning to preach the gospel, and gave him money to help him on his way. A motherly sister expressed fears that some might take advantage of the youth since he was still in his teens, but a good brother who had encouraged him to make the start quoted to the sister Paul's admonition to Timothy, "Let no man despise thy youth," and encouraged the lad to go forward in the work. For a time he united with an older minister in order to secure experience. During the summer of 1849 he worked in his brother's carriage shop, and the next winter began preaching again. In the spring of 1850, friends among whom he had labored presented him with a horse, harness, and a light wagon. For the next few years, like Paul of old he worked with his hands to pay expenses, and preached the word to the people. God has need today for many consecrated young people who will enter self-supporting work.

In the spring of 1852 the young minister settled in Rochester, painted houses from five and a half to six days each week to earn his living expenses, and preached each Sunday. In this manner he had worked for three and one-half years prior to his acceptance of the Sabbath.

Near the close of the summer he became a salesman, selling patent sash locks and holding meetings where his business called him. One Sunday while he was at home he attended. a meeting of the Sunday keeping Adventists where J. B. Cook, in speaking on the Sabbath question, engaged in a tirade against Mr. and Mrs. James White. Mr. Loughborough had never heard of these people, and was led to inquire as to their beliefs and teachings. In the meantime he had become much interested in the sanctuary question and certain points of doctrine held by the Sunday observing group of Adventists of which he was a member. Having learned that a seventh-day minister had preached to two of the churches of his circuit and that a number of his flock had begun to keep the Sabbath, he was much exercised, and prayed over their case. Upon retiring, he dreamed of being in an Adventist meeting. He saw his fellow workers in a dingy room, ill-ventilated, poorly lighted, and dirty. Confusion and discouragement reigned. Their talk was as dark spiritually as the room was physically. A door opened into a larger room, well ventilated, light, clean, and inviting.

A chart hung on the wall, and a tall man stood by it explaining the sanctuary and other questions about which Mr. Loughborough had been exercised. He arose, saying: "I am going to get out of this. I am going into that other room." His brethren sought to keep him from entering the larger room of light. When entreaty did not avail, they began to threaten him and heap abuse and ridicule on him. Entering the large room, he found among others, the members of his two congregations who had begun keeping the Sabbath. The people in this room seemed happy and were rejoicing in the study of their Bibles, which were in their hands. He began to meditate on the difference between the two rooms, and awoke, deeply impressed that he would soon see great light on some of the questions which had troubled him.

On September 25 and 26, 1852, the Sabbath keepers held a conference in Rochester, and one of Mr. Loughborough's group proposed that the two go to the seventh-day meeting. Mr. Loughborough, who was prejudiced against the Sabbath keepers, refused to go. "But," replied the other, "you have a duty to do there. Some of your flock are there. You ought to go and get them out of their heresy. They give a chance to speak in their meeting. You get your texts ready, and you can show them in two minutes that the Sabbath is abolished." Mr. Loughborough agreed to go, selected his texts with which to prove that the law was abolished, and went to the meeting.

On looking around the room he saw the same chart that he had seen in his dream, and beside it stood J. N. Andrews, whom he recognized as the man he had seen explaining its figures. There also sat the members of his flock, just as he had seen them in his dream. Soon Mr. Andrews, in a calm, solemn manner, said he was going to examine the Scriptures supposed to teach that the law was abolished. He then took up the identical texts Mr. Loughborough had selected, and so thoroughly refuted the arguments the latter had in mind that he was left with nothing to say. Instead of speaking against the principles laid down, he left convinced that these people had important truth which he had not yet received. Thus Mr. Loughborough heard the third angel's message for the first time. His brethren, upon learning that he was determined to investigate the Sabbath question, did just, as he had dreamed they would. They resorted to ridicule, unkind criticism, and abuse. This only increased his faith, and thereafter he did not work on the Sabbath. After three weeks of careful and prayerful study he took his stand for the Sabbath publicly, in October, 1852.

During the time of the conference at which Mr. Loughborough had been convinced of the Sabbath truth, Mr. and Mrs. White were on a trip with horse and carriage to the State of Maine. They arrived home on Friday evening, and Mr. Loughborough was introduced to them on that first Sabbath in October. A few days later he wrote to the Review:

"I had supposed there was no Sabbath, and therefore, observed none, . . . and now the Sabbath to me is a delight, and I love to keep God's holy law."

On the first Sabbath he kept publicly, Mrs. White had a vision which lasted one hour and twenty minutes. At the close of this, Mr. Loughborough tells us, she spoke to him about his investigation before he had cast his lot in with them. Some of these things he had never mentioned to any one.

Prior to his acceptance of the Sabbath, Mr. Loughborough had made a good living for his family selling patent sash locks. When he accepted the Sabbath the conviction came to him that he should give up business and devote himself wholly to preaching the message. He tried to make excuse, however, by telling himself that the work of proclaiming this new truth was too sacred for one so unworthy. He accordingly resolved to give his time wholly to business, and set aside some of his earnings to support the preaching of the truth.

As he called on prospective purchasers with this idea in mind he could not sell any goods in spite of his earnest efforts, although builders admitted that they intended to use the locks in their buildings. Frequently, the sales for a five-day week did not yield enough profit to pay transportation expenses to and from Rochester and hotel bills incurred on the road. This soon ate up his little savings of thirty-five dollars, and he did not have enough money to leave Rochester on sales trips.

During this period of depression and discouragement the conviction had been growing on him that he should give his time completely to preaching the third angel's message. Finally, about the middle of December, 1852, when he was down to only a three-cent piece, he attended a Sabbath meeting at Rochester. A cloud seemed to hang over the meeting. Prayer was offered to remove it, and Mrs. White was carried away in vision. Upon coming out of vision she stated that the reason the cloud was over the meeting was that Mr. Loughborough was resisting the conviction of duty. After earnest prayer he decided that if the Lord would open the way, he would go and preach. Peace settled down upon him, he said, as he made this decision. The perplexing anxiety of support for his family melted away. Although he had only three cents and knew not where more money was coming from, he felt the assurance of God's provident care.

Shortly after this decision, his wife, who did not know how low his funds were, approached him to ask for money to buy some matches and a few other minor household supplies. Taking the money from his pocket, he said: "Mary, there is a three-cent piece. It is all the money I have in the world. Only get one cent's worth of matches. Do not spend but one of the other two cents. Bring me one cent, so that we shall not be entirely out of money. You know, Mary, I have tried every way in my power to make this business succeed, but I cannot." With tears, she said, "John, what in the world are we going to do?" Her husband replied, "I have been powerfully convicted for weeks that the reason my business does not succeed is because the Lord's hand is against me for neglecting duty. It is my duty to give myself wholly to the work of preaching the truth." "But," she replied, "if you go to preaching, how are we to be supported?" He answered that as soon as he decided to obey the Lord there had come an assurance that He would open the way. He did not know how it was going to be done, but he felt that the way would be opened.

His wife went into another room to weep. She was gone for an hour, and then went out to make her purchases. While she was out there was a rap at the door, and a stranger from Middleport introduced himself and placed an order for eighty dollars' worth of locks. The commission was over twenty-six dollars, and it was necessary only to carry the order one-half mile to the factory and get it filled. Thus in a few hours from the time he had decided to do his duty, a considerable sum was placed in his hands with which to prepare to enter the field.

When Mrs. Loughborough returned and handed her husband the penny, he said, "The way has opened for me to go out and to preach while you were gone." Then he told her what had happened, and she went out to have another cry of a different nature. On securing his commission he bought a barrel of flour and other supplies and made preparations to enter the work.

At a general meeting the next Sabbath, Mrs. White was again taken off in vision, and she was shown that Mr. Loughborough was correct in his decision to give himself to the work of the ministry.

Hiram Edson, who lived some forty miles east of Rochester, had decided not to attend the general meeting, but on Sabbath morning, while engaged in prayer at family worship, the impression came to him: "You must go to Rochester; you are needed there." He went to the barn and prayed. The conviction was still stronger that he should "go to Rochester." At the close of the Sabbath he took the train, arriving in Rochester after the evening meeting. He told James White his impressions, asking, "What do you want of me here in Rochester?" Mr. White answered, "We want you to take Brother Loughborough and go with my horse, Old Charley, and the carriage and take him over your field in southwestern New York and Pennsylvania." In a day or two they were on their way, and J. N. Loughborough was doing his first preaching in the movement he was to support for nearly three quarters of a century.

1938 END, FOME 251-266